This

digital exhibit shows images of how Kansans responded to the demands and

hardships of life during the 1930s. They had to contend with not

only the economic crisis of the Great Depression but also spates of drought

and dust storms that plagued many Plains states during this decade.

Yet most of the available images as well as the records of the WPA Writers'

Project in Kansas don't dwell on these problems. Rather, they show

ordinary people intent on renewing the land and recovering their lives.

Above all, they show the resilience of people true to their pioneer heritage

who knew they just had to get on with the business of living as best they

could.

This exhibit explores three central themes

of Kansas during the Great Depression: hard times; renewal

and recovery; and resilience. This website contains

both an image gallery and excerpts from the research summaries submitted

by the staff writers who worked on the Kansas Writers' Project for the

Works Progress Administration. Click on the thumbnails below to access

larger versions of the images or PDFs of the excerpts from the WPA Kansas

Writers' Project.

Special Collections and University Archives, Wichita State University Libraries, contains the largest collection in Kansas of materials compiled by WPA researchers, with full or partial records from 50 of the 105 counties in the state. These materials form the basis for the guide originally published in 1939 as Kansas: A Guide to the Sunflower State, and republished in 1984 as The WPA Guide to 1930s Kansas.

The online finding aid to this collection, Papers of the Federal Writers' Project of the Works Progress Administration for Kansas is located at http://specialcollections.wichita.edu/collections/ms/71-01/71-1-a.html.

This digital exhibit is presented as part

of the programming for Soul of a People: Writing America's

Story. Soul of a People

programs are sponsored by the American Library Association in support

of a Spark Media documentary program of the same name to be broadcast

on the Smithsonian Channel HD in Fall 2009. The National Endowment

for the Humanities has provided grant funding to Wichita State University

Libraries for programming in Spring 2009. For more information about

the programs, visit the Soul of a People website

at http://library.wichita.edu/soulofapeople/events.html.

Dust clouds rolling over the prairies, Stovall Studio. Dodge City, Kansas, 1935. Special Collections, WSU

Dust clouds receding after a dust storm, Stovall Studio. Dodge City, Kansas, 1933. Special Collections, WSU

Red Cross volunteers wearing masks during the Dust Bowl drought. Liberal, Kansas. Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory

John Vachon, Abandoned stores. Shaw, Kansas, 1940. FSA

|

Hard Times

The decade of the 1930s Depression was especially hard on Kansas and the neighboring Great Plains states because the economic crisis coincided with drought and dust storms that lasted for much of the decade, particularly in the western part of the state. The late Clifford R. Hope, Sr., a long-time Kansas Congressman, remarked that because of these natural disasters “Kansas and the neighboring Great Plains states got a double dose of misery and calamity”[1] that affected every part of the country during this tumultuous decade.

The worst year in Kansas for dust storms, known as “black blizzards,” was 1935. An article from the April 10th edition of the Garden City Daily Telegram recounts in vivid detail one of the worst dust storms to roll in that year:

The “Black Friday night” duster [on March 15] . . . was equalled if not surpassed by the intensity of the top soil blizzard which swept this region today. After a brief cessation from yesterday’s blow

during the early morning hours, a new storm swept in . . . and grew

steadily worse until it was dark as night before noon. Bright electric

signs could hardly be seen across the street.

Traffic was halted, schools closed, numerous meetings and social

functions postponed and virtually all business in Garden City and

neighboring towns was suspended. Other than grocery and drug

stores most business houses were closed and clerks had returned to

their homes. Only first and second hour classes were held this

morning in the public schools, including the junior college.[2]

A few statistics fill out the grim picture. It should be noted that agriculture was even more central to the state’s economy in the 1930s than it is today. In addition, farmers were already going through tough times during the 1920s, despite the general prosperity of the rest of the country. Things went from bad to worse during the thirties and the total value of agricultural production was only 63% of what it had been during the previous decade. Yields of wheat and corn were generally lower as winds blew off the loose topsoil. There was a severe decline in farm prices for much of the decade. The 1930s is also the only decade when the state as a whole lost population. Many of the problems that Kansans suffered during the Depression were not new, but the boom and bust agricultural cycle that was part of the Great Depression was surely the worst of its kind in the state’s history.

[1] Clifford R. Hope, Sr., “Kansas in the 1930’s,” The Kansas Historical Quarterly, v. 36 (Spring, 1970): 1.

[2] Quoted in Robert W. Richmond, Kansas: A Land of Contrasts, 2nd edition (St. Louis, Mo: Forum Press, 1980), p. 236. |

Town in darkness during a dust storm, Stovall Studio. Dodge City, Kansas, 1933. Special Collections, WSU

Drifts of dust around a farm, Stovall Studio. Dodge City, Kansas, 1933. Special Collections, WSU

Arthur Rothstein, Soil erosion. Crawford County, Kansas, 1936. Farm Security Administration (FSA)

John Vachon, Abandoned farm. Ottawa County , Kansas, 1938. FSA |

CCC construction of Clark County State Lake. Clark County, Kansas. Special Collections, WSU

John Mack Bridge construction. Wichita, Kansas, 1930, Wichita Public Library

Bitting Avenue Bridge, New Deal public works project. Wichita,

Kansas, circa 1935. Wichita-Sedgwick County Historical Museum

Beech aircraft bound for the Philippines. Wichita, Kansas, 1935. Special Collections, WSU

Shoppers at Walker Brothers Dry Goods Company, 129 N. Main Street. Wichita, Kansas, circa 1935. Wichita-Sedgwick County Historical Museum |

Renewal

and Recovery

Public programs for relief and recovery during

the 1930s left an indelible legacy on Kansas agriculture and political

life. Many of the images in this exhibit focus on visible

improvements in agriculture, soil conservation, and public works

projects. Several images reveal the vitality of political

life during the 1930s and the determination of ordinary people just

to get on with the business of living and coping.

The New Deal provided the impetus for better organization and more

cooperation to improve soil conservation. The techniques to

prevent topsoil blowing away were already known in the form of roughening

up the topsoil or getting a cover crop. The challenge was

coming up with a plan that landowners and tenant farmers in Kansas

were willing to follow since the problem could be solved only with

coordinated, continuous and broad-based effort. The dire need

prompted many to push for compulsory measures, and the legislature

passed a bill in 1935 that required landowners to take care of their

land. If they failed to do so, the county would charge the

costs back as additional taxes. Even though the bill was declared

unconstitutional, its re-passage in amended form two years later

marked a turning point in the willingness of owners and tenants

to work with state and government agencies for the common good.

Farmers and other private citizens frequently railed about the extent

of governmental intrusion into their lives. They resisted

legislation that regulated crops and livestock such as the Agricultural

Adjustment Act, but the fact of the matter was that allotment checks

and other New Deal subsidies enabled many people to hold onto their

farms and survive the worst of the Depression. People both

needed and wanted the help, at the same time that they resented

their dependence on public funds.

The 1930s was one of the few decades in the twentieth century that

Kansas enjoyed the give and take of active and lively contests between

the two political parties for both state and national offices. The

presence of a viable third party candidate for governor in 1930

and 1932, John R. Brinkley, added both spice and controversy to

the mix. Brinkley was a doctor specializing in male sexual

rejuvenation using goat glands who advocated populist issues, including

free textbooks, tax equalization, community health clinics, and

a lake in every county to increase rainfall.

Democratic candidates won the governorship twice during the decade,

Harry Woodring in 1930 and Walter Huxman in 1936. Another

Democrat, George McGill, was a U.S. Senator from 1930-1938. Kansas

supported Franklin Roosevelt in 1932 and in his 1936 landslide victory

even though his opponent was Kansas governor and popular native

son Alf Landon. This was one of only three times in the twentieth

century that Kansas voted for a Democratic candidate for president.

Images in this exhibit also document the lively grass roots political

organizing that characterized Kansas political life in this decade.

Examples include two meetings in southeastern Kansas in 1936: a

gathering of wives of Farm Labor Union members in Galena and a political

demonstration of the unemployed in Columbus. |

CCC members. Clark County, Kansas. Special Collections, WSU

Removal of Ackerman Island, New Deal public works project. Wichita, Kansas, circa 1933. Wichita-Sedgwick County Historical Museum

View of New Municipal Beach, South Riverside Park. Wichita, Kansas, 1938. Special Collections, WSU

Mantle factory workers at the Coleman Company. Wichita, Kansas, 1938. Special Collections, WSU

Polar Bear Frozen Custard, Central and Oliver Streets. Wichita, Kansas, circa 1938. Wichita Sedgwick County Historical Museum |

President and Mrs. Roosevelt arriving at Union Station. Wichita, Kansas, 1936. Wichita Public Library

|

Arthur Rothstein, Wives of Farm Labor Union members. Galena (Cherokee County), Kansas, 1936. FSA

|

Arthur Rothstein, Political demonstration of the unemployed. Columbus, Kansas, 1936. FSA

|

Arthur Rothstein, Striking zinc miners. Cherokee County, Kansas, 1936. FSA |

John Vachon, Farmer’s Union Coop grocery store, recipient of an FSA loan. Centralia, Kansas, 1938. FSA |

Russell Lee, FSA supervisor and client examining silage quality from trench silo. Sheridan County, Kansas, 1939. FSA

|

Russell Lee, FSA home supervisor conferring with wives of FSA clients. Sheridan County, Kansas, 1939. FSA

|

Russell Lee, Mr. Johnson, FSA client, building a small dam of board and tumbleweed. Syracuse, Kansas, 1939. FSA |

Kansas farm women’s literary meeting. U.S. Department of Agriculture

Kansas Diamond Jubilee celebration. Wichita, Kansas, 1936. Wichita Public Library

Russell Lee, Tightrope performers at 4-H Club fair. Cimarron, Kansas, 1939. FSA

John Vachon, Tenant farmer and FSA rehabilitation client. Jefferson County, Kansas, 1938. FSA

Chinese and English New Year greeting card with photographer M.S. Fong’s self-portrait. Wichita, Kansas, circa 1939. Wichita-Sedgwick County Historical Museum

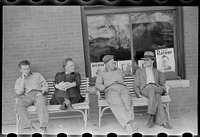

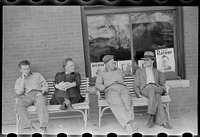

John Vachon, Men talking politics in front of the hotel. Oskaloosa, Kansas, 1938. FSA |

Resilience

Despite the severity of the economic crisis and the dust bowl in Kansas during the Great Depression, the iconic images of this period are, paradoxically, not those of despair or abject poverty but resilience. Oral testimonies and other written accounts, including the records from the WPA Writers’ Project in Kansas, confirm the accuracy of this attitude. Selections from the Kansas Writers’ Project in Special Collections and University Libraries, Wichita State University Libraries, are included below.

Most noteworthy were people’s willingness to pull together and their reluctance to leave Kansas. The following three comments by Kansans who lived through this period get to the heart of the matter with an understated eloquence that evokes the quiet strength of those who felt they had no choice but to persevere.

A homemaker in western Kansas reflects on the rhythms of social life in the mid-1930s that brought people together:

Strange as it may seem we had fun. I can remember the days when

the wind and dirt would blow all day until along about sunset when

the wind would go down and the air would clear. One of the neighbors

would drive into the yard . . . and say “come over for supper.” We

would hurriedly fix a dish of something to take and the whole family

would go; after supper we would play cards and have a really good

time. We also had party dances in our homes; there would be two

or three men available who played a violin and a guitar; we would

move enough furniture out of the front room so we would have

enough room to dance. . . . Most of us managed to buy a radio, which was something new, and spent many a night listening to the programs and music.[3]

To one resident of western Kansas, what mattered most were the bonds created by shared hardships that mattered more than who people were or how much or little they had:

All were equal with no money. In sickness or problem times all helped – a people-to-people relationship, what the government says

we need to do now to solve some of our social problems. We had it then. . . . All were accepted, even if you could not pay your bills or if

you were a sly businessman, you all belonged.[4]

In a 1941 article explaining why most people in western Kansas chose to stay, local writer Ada Buell Norris reflected:

Why do we stay? In part because we hope for the coming of moisture, which would change conditions so that we again would have bountiful harvests. And in great part, because it is home. We have reared our family here and have so many precious memories of the past.

We have our memories. We have faith in the future, we are here to stay.[5]

The responses of these people, like the images and WPA Writers’ Project excerpts displayed here, reveal the optimism and steely determination that drew people out to Kansas in the first place and instilled in them the resilience and courage to transform adversity into opportunity.

[3] Ibid., p. 239.

[4] Ibid., p. 252.

[5] Ada Buell Norris, “Black Blizzard,” Kansas Magazine (1941, Manhattan, Kansas), p. 103, quoted in Hope, “Kansas in the 1930’s,” p. 7. |

McKenzie Midget Auto. Wichita, Kansas, circa 1932. Wichita-Sedgwick County Historical Museum

KANS Radio Broadcast. Wichita, Kansas, 1938. Special Collections, WSU

Russell Lee, Dance poster in drugstore window. Syracuse, Kansas, 1939. FSA

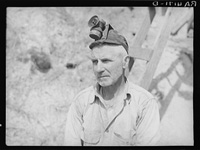

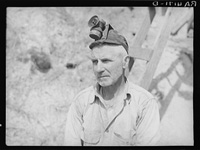

Arthur Rothstein, Coal miner. Cherokee, County, Kansas, 1936. FSA

Friends posed for group portrait. Wichita, Kansas, 1938. Wichita-Sedgwick County Historical Museum

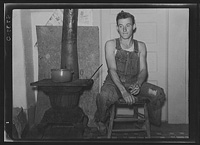

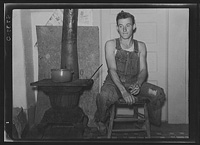

John Vachon, Young farmer. Jefferson County, Kansas, 1938. FSA

|

Birger Sandzen in front of his mural “Kansas Stream.” Special Collections, WSU

|

District School” print by Herschel Logan. Salina, Kansas, 1934. Special Collections, WSU |

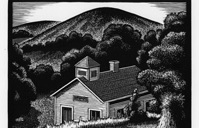

“Kansas Hills” print by Herschel Logan. Salina, Kansas, 1934. Special Collections, WSU |

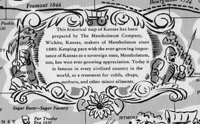

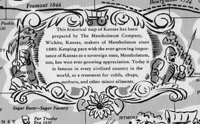

Kansas map cartouche by Robert Aitchison. Wichita, Kansas, 1936. Special Collections, WSU |

“Development of Aviation,” WPA KS Writers’ Project, Special Collections, WSU |

“Kansas Wheat Field,” WPA KS Writers’ Project, Special Collections, WSU |

“Wheat Harvest,” WPA KS Writers’ Project, Special Collections, WSU |

“Cave on Rutherford Farm,” WPA KS Writers’ Project, Special Collections, WSU |

“Valley Center,” WPA KS Writers’ Project, Special Collections, WSU |

“American Indian Institute,” WPA KS Writers’ Project, Special Collections, WSU |

“St. Peter Claver Parish,” WPA KS Writers’ Project, Special Collections, WSU |

“Syrians,” WPA KS Writers’ Project, Special Collections, WSU |

“Negroes,” WPA KS Writers’ Project, Special Collections, WSU

|

“James Ellis Pope, former slave,” WPA KS Writers’ Project, Special Collections, WSU |

“A Tramp Speaks,” WPA KS Writers’ Project, Special Collections, WSU |

“Hazel Branch,” WPA KS Writers’ Project, Special Collections, WSU |

“Helen Houston,” WPA KS Writers’ Project, Special Collections, WSU |

“Madeline Aaron,” WPA KS Writers’ Project, Special Collections, WSU |

“Kathleen Kersting,” WPA KS Writers’ Project, Special Collections, WSU |

|

Credits:

Text and image selection by Dr. Lorraine Madway. Exhibit design by Dr. Lorraine Madway and Mary Nelson. Digital images created by Mary Nelson, Kelly Dyer, Elysia Schooler and Deb Koons.

Images in this digital exhibit

may be in the public domain or under copyright which is protected by U.S.

Copyright Law (Title 17, U.S. Code). Images in the public domain are made

available for use in research, instruction and private study. Copyrighted

materials may be used for research, instruction, and private study under

the provisions of Fair Use, outlined in section 107 of copyright law.

Publication, commercial use, or reproduction of a copyrighted image that

does not fall under the provisions of Fair Use or the accompanying data

requires prior written permission from the copyright holder. User assumes

all responsibility for obtaining the necessary permission to publish (including

in digital format) from the copyright holder. If publishing this image

in print, electronically or on a website, for research, instruction or

private study, please use the citation "Courtesy of Special Collections

and University Archives, Wichita State University Libraries" and

inform us of your use at specialcollections@wichita.edu. For other uses

of materials, see Statement on Use and Reproductions, http://libraries.wichita.edu/ablah/index.php/aboutsc#use.

May 2009; April 2011; January 2012; April

2012; August 2012

Special Collections and University Archives

Wichita State University Libraries

Contact us

|